GreenBiz- Sustainable MBA

The Sustainable MBA

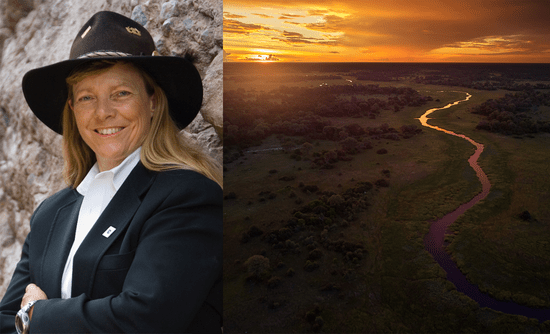

For our finer future: Hunter Lovins on both the changing atmospheric and political climate

L. Hunter Lovins, president and founder of Natural Capitalism Solutions, believes that citizens, communities and companies, working together within the market context, are the most dynamic problem-solving force on the planet.

A champion of sustainable development for over 35 years, Lovins has consulted on business, economic development, sustainable agriculture, energy, water, security and climate policies for scores of governments, communities, and companies worldwide.

Time Magazine recognized her as a Millennium Hero for the Planet, and she has won the Rachel Carson and Right Livelihood awards, among dozens of others.

Lovins has co‐authored 15 books and hundreds of articles. Her best-known book, “Natural Capitalism,” won the Shingo Prize. It has been translated into a more than three dozen languages and summarized in the Harvard Business Review.

Bard MBA Director Eban Goodstein spoke with Lovins about her trailblazing work in sustainability and her latest book, “A Finer Future,” released in September.

Eban Goodstein: Your book “Natural Capitalism,” published in 1999, was seminal in launching the sustainable business revolution. This new book strikes me as being even more Important. How has your thinking evolved from the late ’90s to today in the Trump era?

Lovins: When we wrote “Natural Capitalism,” to some extent we were going on guts and a few examples. For instance, Ray Anderson set out to make Interface the first company of the next industrial revolution. He and I were sitting together in 2001, and he looked at me in this puzzled sort of way and said, “Everything I’m doing to make Interface a more sustainable company is enhancing shareholder value.”

That wasn’t why he did it but that was the outcome. And what he did became the three principles of natural capitalism. He started with efficiency, using all resources dramatically more productively, then moved on to biomimicry, trying to redesign how he made and delivered all of his products, and finally committed to being regenerative.

He proved that doing this would be more profitable, and we now have abundant evidence that that’s true — which we didn’t really have in 1999. CDP showed in 2014 that the companies that were leading in measuring and managing their carbon footprint had 18 percent higher return on investment than the laggards, 67 percent higher than companies that said climate change was not real. There are now well more than 50 studies showing that the companies that are leading in ESGhave, take your pick: the highest stock value; the fastest growing stock value; well outperform the market; outperform their peers; and have more engaged workforces (a better engaged workforce will give you 16 percent higher profitability, 18 percent higher productivity).

But now it’s 20 years later, and we’re losing every major ecosystem on the planet. We’re in a climate crisis, so whatever we did wasn’t enough. We thought, just put out the numbers, put out the argument, put out the logic and people will change. And indeed business has, in many ways, stepped up.

Essentially every major business has a chief sustainability officer. Businesses are cutting their costs and doing all of the more responsible things because they’re profitable. Yet we’ve been flying in the face of a narrative that says that it’s good to be greedy, and that we don’t really need government because markets are perfect, and that in this perfect market, “you against me” will somehow aggregate to the greater good for all of us.

The point of “A Finer Future” is that we have all of the technologies we need to solve the crises facing us, so let’s go, let’s build a finer future. But to do this we need a new story of who we are as human beings, what it is that we want, and how it is we can best achieve a world in which all of us flourish — as opposed to today’s world where eight men have as much wealth as the 3.5 billion poorest people on earth.

Goodstein: You’re exposed to so many people doing so many interesting things that could get us out of this mess. Can you give us a taste of what might be coming down the pike?

Lovins: My friend Tony Seba says that inevitably by 2030, for fundamental economic reasons, the world will be 100 percent renewably powered. The first driver is the fall in the cost of solar. The second driver is the fall in the cost of storage, of batteries. China has 20 gigafactories coming online in 2020 to churn out batteries. And 500 million businesses around the U.S. would benefit now from putting in batteries so that at peak time they don’t have to pull electricity from the grid.

Tony’s third driver is the electric car. China has said it’s going to phase out the internal combustion engine, and General Motors has said that its future is electric. There are now 500 electric car companies in China — that’s a quarter of the world’s car market. Finally, the fourth driver is the autonomous electric vehicle, which Tony says will cut costs tenfold below what it costs you today to buy fuel, maintain and insure a private vehicle.

Put all of these technologies together, and inevitably by 2030 the world is 100 percent renewably powered. We’re looking at a potentially very attractive future where we’ve solved half the climate crisis.

Goodstein: How do we tunnel through the barriers that are holding these technologies and businesses back?

Lovins: Companies that work together — for example, on pre-competitive solutions to problems that face their entire industry — do better than those that try to stand alone. And so we walk through what John Fullerton calls the principles of a regenerative economy (PDF), and from this argue that we can build a finer future. When we do this, again, it’ll be vastly more profitable and will be a hell of a lot more fun to live in.

This Q&A was an edited excerpt from the Bard MBA’s Nov. 2 The Impact Report podcast. The Impact Report brings together students and faculty in Bard’s MBA in Sustainability program with leaders in business, sustainability and social entrepreneurship.

Leave a Reply